The McMullan Shelter

The First Store

About the Author

The McMullan House

The Mantelpiece

The McMullan Shelter

The logs of the newly constructed McMullan shelter came from Jeraldine’s grandmother’s home, which, within the past couple years, caught on fire and whose remains were to be torn down and discarded.

But with a little last-minute negotiating, Jeraldine purchased the remains, with the intention of somehow incorporating them into the home she had built.

On the inside of the shelter, there are a couple benches and a table, all made out of the wood from the old house.

The back wall has a fireplace, made of stone from the Morris-Tata farm that Jeraldine and Kendall currently live. It is their way of mixing the McMullan family property, with that of the Morris family. The two sides of her mother and father, reunited again.

Pictured below is the view standing inside the shelter. In the distance are the Blue Ridge Mountains. The garden that Kendall has made can be seen to the right. ◊

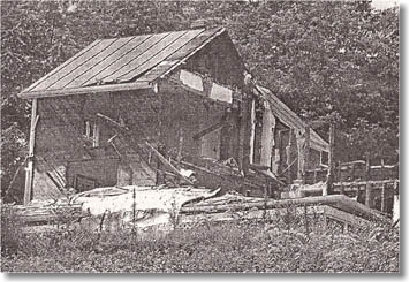

Where it all Began: The First Store Now know as the Blue Ridge Pottery, this building was the first store that the Morris family owned. John Ollie Morris ran it with his brothers, Grover and Jean, and his father, Ezekiel “Bud”. A few years later, the family sold this building in order to rent, and eventually buy, a different store on Main Street in Stanardsville. ◊

KATHERINE TAYLOR is an ambitious freshman majoring in English and minoring in Journalism. Katherine plans to attend graduate school, perhaps following in her father’s footsteps by seeking a graduate degree at Clemson University. Katherine aspires to one day become a magazine writer. Her home is buried away in Greene, Virginia, located in the heart of the Shenandoah Mountains. Katherine has lived in Greene all of her life and can never get enough of the fresh mountain air. In her spare time, Katherine enjoys reading outside with her Nook, spending quality time with friends and family, and hiking up the trails of Skyline Drive located off the Blue Ridge Parkway.

—Jane Gregorski

This is the McMullan house before it was moved up on a hill in order for a small shopping center to be built. The white boards are covering up logs, which is what the McMullan Shelter in Jeraldine’s backyard is created from. This is the same building where Jeraldine sat in an upstairs window and watched the “flames licking the sky,” during the Stanardsville fire. Kendall recollects visiting there on summer vacations, and hunting for crawfish in the water behind the house.

Pictured below is the home after it had been moved, and then burned. Luckily, Kendall made an inquiry and was able to save some of the remains before it was entirely demolished. ◊

from "The House on the Hill"

During the depression, when money became tight for everyone, and some families were worse off than others, the brothers decided to sell the living room mantel for five hundred dollars, a really large chunk of change for that time. “I remember I was very small when my father was going to sell it, and I said, ‘Please, don’t sell it!’ and they just laughed,” Jeraldine shrugged her shoulders, thinking back.

"The House on The Hill: A Mother & Daughter Reunion"

by Katherine Taylor

—“We had a farm, and it was a 360-acre farm that she lived on at that time," Jeraldine recollected. “Word had evidently gotten out that my grandmother fed people. She would get up so early, so she could make ham biscuits. They had plenty of meat on the farm. She would get up and make these ham biscuits and pies. "

Since it’s such a small community, it is safe to say that it’s basic knowledge to know who lives where, how long they’ve been in Greene, and what their story is. Since I was born and raised there, it’s been a sort of assurance to have that kind of knowledge, and to feel close to the people that have surrounded me. Until several years ago, that is. That’s when the house on the hill was built, and a new guessing game began.

“Who lives there?”

“Why’d they build something on THAT?”

“I thought that was family land?”

Rumors and gossip flew, and the more people speculated, the crazier the ideas became: Was it Steven Tyler? The Rock? Bill Gates? Where some people came up with these theories, I do not know, but a phenomenon had swept through the county.

It was a common sight to see people speeding down the road, slow down as they approached the house, and let their tires roll as they passed by, peering up the driveway in an attempt to catch a glimpse of the owner. After a few months passed by, most inquirers gave up, and the mystery just lingered, seemingly forever unsolved.

What most of Greene County didn’t know, was that they had been partially correct: the farm was family land, and it was a member of that family that had come back to fulfill a dream.

A Mother & Daughter Reunion

It was Kendall who encouraged her mother, Jeraldine, to do the one thing she had always wanted: build a house on the land she had cherished from her childhood. One day, the mother and daughter drove from their home in Virginia Beach to Stanardsville, Virginia, to the land Jeraldine had always pictured in her mind. Kendall at the wheel, they drove up a grassy hill in their Buick, before stopping at the top and stepping outside. Turning to her mother, Kendall said, “Stand where you want your house built,” and, wading through the grass and hay, Jeraldine stood in the exact spot of farmland that her home covers this day.

In 2004, the builders finished the house, and the family moved some of their belongings there. At that point, the house was for weekend visits, and Kendall came when she had breaks from school. Two years later, Jeraldine told her husband, Bob, that she wanted to move back to Greene. Because of his job as a representative in the House of Delegates, Bob couldn’t leave the district he was representing.

That’s when Kendall stepped in. “I never knew I fell in love,” she said. Understanding how many sacrifices her mother had made for her over the years, Kendall sent in an application to the Greene County School System. Now, both ladies live on the Morris-Tata Farm, which is also called Pioneer Haven because of Jeraldine’s determination to see the building of the house through, no matter what weather stood in her way.

Like I said, in a small town, it usually isn’t difficult to figure these things out. So, with a little asking around, we found that Kendall was to be a new gym teacher at the high school, moved here from Virginia Beach to help take care of her mother. From then on, it was pure luck, and the Tata’s family kindness that helped me to learn their story.

A Mysterious Mantelpiece

Just visiting the house on the hill was exciting on its own. I was anxious to see what it looked like from the inside. The only view that I had had, and everyone else that I knew had for that matter, up until that point, was of the two-story house, with its windows glinting in the sunlight, porches wide and surrounding the front and the back of the structure.

Looking around, the first thing I noticed was the view: absolutely gorgeous. The house is in the middle of a field, on top of a hill, surrounded by emerald grass, the mountains rising against the clear, blue skies.

A backdoor opened, and Kendall stepped out onto the winding porch, waving. She is slender, with tan skin, and huge smile. After a hug, and kiss on the cheek, I walked into an open living room with high ceilings, and windows that overlooked the backyard and scenic view beyond. Immediately after stepping over the threshold, my eyes were drawn to the mantelpiece. It was huge, about seven feet tall, or more, and was a deep forest, green color, with intricate designs. All around the room there looked to be items that had been passed down, as well as pictures. There was one, in particular, of a brick building I had driven by many times.

Kendall’s mother, Jeraldine, was right inside the door. Shorter than her daughter, and also smiling, she hugged me, and, like Kendall, kissed me on the cheek. Both ladies invited me to sit, Kendall on my left on the leather sofa, Jeraldine across from me, with the ornate mantelpiece standing tall behind her. The coffee table that was positioned in-between us had dishes of cookies, crackers, and a variety of dips—all delicious. After accepting a glass of water, I chatted, slowly getting to know the person so many people wondered about.

To me, Jeraldine seemed familiar. Not just in an “I think I’ve seen you around town” way, but similar to the people I had grown up around. She reminded me of people like my grandparents and great grandparents that had been citizens of the area their whole lives. After all the gossip and ideas everyone had, it seemed laughable to think that anyone else. The entire time I visited with them, I thought to myself: how could this sweet woman be thought of as an insignificant character in all the storylines people had imagined?

Kendall paused then looked at her mother and said, “Mom, why don’t you tell her about the mantelpiece?”

“Oh, yes,” Jeraldine replied, sitting up straighter. “It’s something that is very special to us,” she settled back into her chair and took a sip of water from the glass sitting on the table.

“In 1825, or thereabouts, a gentleman named Sheler came down from the mountains,” she began. “He was a descendant of a hessian solder who had hid out in the mountains in the Revolutionary war because he didn’t want to go back to Germany. There were about twenty-one of those hessian soldiers that said they didn’t want to go back to Germany, so they stayed in the mountains. I guess you could say they were A.W.O.L. from the Revolutionary War,” she laughed. “Eventually a descendent came down, and built a brick house.”

She gestured to a drawing of an older house that I had driven past many times. It was a two-story building a few stone steps leading up to a porch with white columns standing tall.

It was where her grandfather, Ezekiel Morris, and her grandmother had lived with their three sons, one of them her father. After the boys were grown, and Ezekiel had bought a store building in Stanardsville, a small building made of wood, it’s boards painted white, they moved closer to town, and left the house boarded up.

Some years later, during the time of the depression, the brothers sold that same house to a doctor who lived over the mountain in Harrisonburg. This man did not like the intricate mantelpieces that stood in the downstairs living and dining rooms. He planned, instead, to insert new ones made of native fieldstone. The brothers obliged, and removed the pieces, storing them away for safekeeping. That is where they ran into some problems.

“When my father [John Ollie] to store it, he had a problem. He didn’t know what to do. He finally decided that he would store it in the upstairs [of a stucco building on the corner of main street] because the upstairs was not used. So, he had the window taken out upstairs, and downstairs he had friends of his, standing on the street with the mantelpiece and heavy rope.” There were men below with the mantel, and some upstairs, at the opening the window left, ready to guide the object as it was pulled up. “You can still see the rope burns because we never had any of the paint taken off,” she informed me. “We left it as is because that would be more true of the times.”

During the depression, when money became tight for everyone, and some families were worse off than others, the brothers decided to sell the living room mantel for five hundred dollars, a really large chunk of change for that time. “I remember I was very small when my father was going to sell it, and I said, ‘Please, don’t sell it!’ and they just laughed,” Jeraldine shrugged her shoulders, thinking back.

“When the last of the brothers died, we didn’t do anything with it. It stayed in the old stucco storehouse for thirty years,” she said. “Then the last of the brothers, my uncle Jean, who was the youngest one, died. We decided to divide his things that he had left, and this is one of the things,” Jeraldine motioned to the mantelpiece behind her.

In 1977, the nephew and four nieces gathered together, scribbled down numbers one through five on scratch pieces of paper, and threw them all into a hat. From there, proceeding from oldest to youngest, they each randomly reached in and drew a number out, signifying which order they would choose which possession they desired to claim. Although she was the youngest in the group, Jeraldine pulled out the number one.

“I was really lucky, I thought, and chose the mantelpiece,” she smiled. “Later, I heard that nobody else wanted it anyway because it was so big,” laughing she leaned back in her chair. “I was just delighted to get it. It was something that I remembered from my childhood, from that house. So, I was really pleased.” The mantel was put in the upstairs of the stucco building in about 1932, and stayed where it was for about twelve years after the drawing because it was upstairs and so difficult to get to. “My brother-in-law and husband decided in 1989, after I complained a lot about not having it, to bring it down,” Jeraldine laughed.

Instead of repeating the process of using ropes and such, they had to take out a plasterboard wall that had been added after the original structure had been built. After the mantel was out, they had it shipped to Virginia beach where she and her husband were living at the time.

Glancing over at the fireplace, Jeraldine slightly shook her head. “It was really not pretty at all. It was full of cobwebs, dirt, dust, and it was grey from being dried out, I think,” she continued.

“A friend, whose really an antique lover, and I were in the garage, trying to clean the mantelpiece with tooth brushes and water and so forth, when a friend of Kendall’s came across the street and said ‘Ms. Tata, why don’t you use lemon oil on that?’”

Turning to her friend, Jeraldine said, “’Well, Frank, what do you think?’ And he replied, ‘Well, it can’t hurt it.’ So, we put lemon oil on it, and it looked like it drank it,” she exclaimed. “ It was so dried out, so in need of oil. We put the lemon oil on, and the colors came out, and it just was so much better.”

Gazing at the mantelpiece she spent so much time thinking about, working on, and placing in her home, Jeraldine said thoughtfully, “A lot has faded, you can tell, but a lot of the character of the mantel has remained, and we’re really proud to have it.”

Hometown Dreams

With such a reminder of family history and childhood memories, right at her fingertips, it’s not difficult to figure out why Jeraldine dreamt of returning to her hometown. According to her daughter, it had always been in her plans: “Greene County has always been important to my mom, and although she has been away from her family, she has always intended to return home.” And, with Kendall’s help, Jeraldine was able to do just that. After buying shares of her uncle’s farm, she was able to build a house on the land she had visited as a child.

It couldn’t have been easy for Kendall to leave her job as a teacher, friends, and home in Virginia Beach to take care of her mother in a small town, but even though she may not be a local, she is not completely unfamiliar with the area, having spent time in Stanardsville when school was out. “When I was a young child, our family vacations were to Greene County and Charlottesville to see our relatives. We did not go to theme parks or out west or to big beaches. We simply came to this area because it was important to my mother that her children know where she came from, how proud she was of her people and where she grew up. She would talk of her upbringing fondly and say she was from the era where people pulled themselves up by their bootstraps.”

And that was exactly what Jeraldine had witnessed growing up: hardworking people pulling themselves through hard times, and not just giving up because it was challenging. Everybody had a responsibility. Everybody played a part.

It was actually her grandfather, Ezekiel Bud Morris, who really started the family business when he purchased a store on Main Street from Thomas Gibbons in 1912, after renting the building for years. It was a large brick building, with white columns in the front, running all the way up to the roof. According to Jeraldine, “The Gibbons family had purchased the lot from Mr. Ham some years before. It was Mr. Ham’s garden lot. Mr. Ham sold the lot with certain qualifications. For instance, no windows could be put in the building that faced his property. You will notice there are no windows in the building except on the front and the Ford Avenue side.”

“The store was named E.B. Morris and Sons. Then, after E.B. died, it became E.B. Morris’s Sons. My Dad and Uncle Jean ran the store until my father’s death in 1947.

“The store sold everything. Everything people needed, like groceries. They even sold pickled herring in a big barrel in brine. I remember that!” she exclaimed, settling back in her chair.

Those items weren’t the only things they sold in the store. Along with groceries, flour, and turpentine, there were men’s dark suits and shoes because whenever someone died, people would buy them a new suit to be buried in. Other clothing item included men’s and ladies shoes, and men’s hats. In those days, most ladies made their own dresses, although the store had a sizeable inventory of ‘goods,’ which was material. Although most women chose from the large selection of ‘goods,’ some people would even create clothes from feed sacks that were made out of cotton. There store carried all sorts of feed that people would buy in order to feed their chickens.

“During the depression people had a difficult time because there wasn’t much cash, so the store had a bartering system, and you would bring in all of your eggs that you had for that week, and you could get so many yards of material, of ‘goods’ for the eggs that you brought in. Or you might get coffee,” she pondered. “I would say most people used the bartering system. Sometimes, though, they would turn their eggs in for cash because they may need the cash for something else.”

John Ollie and Jean also allowed them to sell them items like wool and walnuts. Store-goers would go out and pick out whatever walnuts they could find. Sometimes they would crack pounds of them and bring them in so they could get paid.

Not only did E.B. Morris’s Sons sell material items and groceries—they had a kind of service station as well. That was were they sold Dodge cars and Sunoco gasoline for twenty cents a gallon.

Almost right across the road is the Grace Episcopal Church, where Jeraldine attended service and Sunday school as a child. “My father, since he had a business right across the street, would go up there about six o’clock: he was responsible for the furnace on Sundays. The store wasn’t open on Sundays. That’s a new thing. Then, everything was closed on Sunday,” she explained. “Everybody had a chore. My mother and aunt cleaned the church one week, and the next week two more people would. The ladies divided the chores among themselves.”

It was a time when families and the community worked together in an effort, to be successful, through thick and thin. This was proved when the town burned in 1929. “We lived down the street in a red brick house, and the fire was so intense, my mother and father took us, my sister and me, down to my grandmother’s,” she recollected. “She kept us, and I remember sitting in her upstairs bedroom window. They had sills that were big on windows at that time, and I sat in the window, and watched the flames just licking the sky. It’s something you never forget, if you saw it.”

Many of her childhood memories included her grandmothers. These were even of little details like the sugar cookies that were stashed in a large jar. Or sitting backwards in rocking chairs, singing whatever tunes came to mind. Her Grandmother Morris lived on a farm, and her Grandmother McMullan in house down the road, but each was special, each loving. But not all memories are what can be classified as happy.

Hungry Times

Like the scare with the fire, it wasn’t always easy times in this simple town. Born in the late twenties, right before the depression hit the small community, Jeraldine has memories of the struggle and heartache that affected many around her. “I can remember, families, whole families, walking down the highways, “ she says, fingers clasped in her lap. “And the highway was not called the highway, it was called the ‘pike’ and that came from ‘turnpike.’”

Since it was a rural community, most people did not live side by side. There were many acres of farmland that separated neighbors from each other. Walking down the dusty “pike,” a man came, a little blonde girl set on his shoulders, her young legs not able to keep up. He was accompanied by his wife and at least eight children, all ragged and worn down, just trudging along, in search of a place they could go, any place.

“We had a farm, and it was a 360-acre farm that she [Grandmother Morris] lived on at that time, “ Jeraldine recollected. “Word had evidently gotten out that my grandmother fed people. She would get up so early, so she could make ham biscuits. They had plenty of meat on the farm. She would get up and make these ham biscuits and pies.

“I used to think it was amazing what she did. She’d bake double-crust apple pies, and they were always the same kind: apple pies, because they had lots of apples. She would stack them, this double-crust pie on that one and just keep going. She had as many as seven pies stacked together, and when she would cut them, she’d cut down through the whole stack. All these pieces because the people were really hungry when they stopped there. I guess you might say that that was her contribution to the depression.”

These families would come and sit on the front porch that ran cross the entire front of the house, placing themselves on the steps, wooden railings, or the two big, flat topped pillars. Although Jeraldine’s grandmother was more than willing to help others in need, she didn’t invite the strangers into her home because she wanted to keep it a secret that there wasn’t a man that lived there too. Instead she would have them sit, eat, and drink the fresh milk that was brought from the springhouse.

All through this time, Jeraldine served as her grandmother’s helping hand, learning firsthand what it’s like to see true need, not just want, and acknowledges this saying, “That’s one of my early, fascinating memories.”

Seeing all the families that just wanted a meal is very humbling, and by seeing this firsthand, helped her realize what is really important in life. Still, having this sort of information doesn’t keep a child from wanting the newest toys. “My friend, Nancy Blakey, had a pair of roller skates. Finally, at Christmas, I got some, and they were sort of fascinating to me,” she stated, looking at me. This was because they weren’t like the skates that are out now. These were metal, and had to be fastened to shoes. That was what the key was for. It was supposed to be turned until they are the right size.

Pushing Forward

It was soon after that time that bicycles became popular, but, unfortunately, Jeraldine wasn’t allowed to have one: “My dad would never let me have one because he thought that I’d run out in the street and be killed. He was just afraid for me.” He also didn’t have to worry about Jeraldine disobeying him. She was always striving to help her parents, respect them, and learn from them.

“I remember best, and I’ve thought about this a lot,” she said, gazing over my shoulder. “I remember following my mother around and watching what she was doing, and I learned a lot from that. I didn’t talk much. It was the era of ‘children ought to be seen and not heard.’”

Jeraldine’s parents were a huge influence in her life. Her father was born in 1878 near the Blue Ridge Mountains, where he, his parents, and his two brothers, Grover and Jean, lived until they eventually moved closer to town. Her mother, on the other hand, was born on the other side of town, in the McMullan homeplace on South River—the place where John Ollie Morris and Edieth Kendall McMullan met for the first time—a story which Jeraldine looks back on fondly.

“One day, when Ollie was twenty three, he was delivering sacks of chicken feed to the Jack McMullan home where he saw a beautiful two-year old little girl. He said, ‘Mrs. Mac, that is the most beautiful little girl I have ever seen. I think I will wait until she grows up and marry her.’ They laughed then, but when Edieth Kendall was eighteen, and John Ollie was forty-three, they were married. Edieth and Ollie had two daughters: Ollie Kendall and Martha Jeraldine.”

“Often I think of my parents and always with the thought of how bessed I was and am to have been their child. My father was kind, gentle, caring, and a wonderful provider of material needs and, even more importantly, of love of family. My mother was gifted in her ability to train her children in ‘they way they should go,’ their education, morals, care of home, courtesy, kindness, wisdom, and spiritual training. She was beautiful and her smile glowing. We always knew we were greatly loved.”

And it was from that watching and listening that she came to learn that life isn’t about giving in—it’s about pushing forward, and still having respect for the ones that do just that. Today, she still spreads those lessons to other people in the community, whether it be giving a talk at the historical society or contributing at D.A.R. meetings.

Not only is she surrounded by history—it seems to find her as well. Her Grandmother McMullan’s house, the one that she and her sister took shelter in when the town was on fire, was moved a short distance in order for a small shopping center to be built. For years, it has sat to the side, growing older, tenants coming and going. Eventually it caught fire, and was ordered to be torn down. Kendall, passing by one day, saw what was happening, and stopped to ask what was going on. It was then that she discovered that the house had originally been made out of logs, only to be covered up over time. Running back home, Kendall explained to Jeraldine what was going on, and after a lot of debating and negotiating, they were able to purchase the salvageable logs. Next to their garden in the backyard, the McMullan shelter stands, built from the original timber from Jeraldine’s grandmother’s home, another piece of family history returned.

On a warm and breezy afternoon, with Kendall at the wheel, myself in the front passenger seat, and Jeraldine in the back, we rode around Stanardsville, both ladies pointing out places where their family members had worked and lived. Together we visited the brick house that Jeraldine’s mantel had belonged to for so long, the first store building that her father’s family had owned, the Grace Episcopal Church that she had gone to as a child, where her family’s store had been located on Main Street, and the graveyard where her parents were buried. I was surprised when Kendall and Jeraldine lead me over to the graves of her parents, mostly because my great grandfather and great uncle were buried only a few feet away. Standing in that cemetery, it hit me once again how little I knew about this town I carelessly call home. All those years I had prided myself on knowing everything about it, when there is still so much I haven’t discovered.

Maybe it’s because I see so many familiarities between her family and my own, that I feel Jeraldine and I are alike. The business that my great grandfather ran was somewhat the same to that of her family. I recognize the places she talks about, and have heard some of the same legends about our town, but yet, she has made me see it in a new way. With every visit there is a new story, whether it be sitting in their living room or riding down the county roads, some detail is forever changed in my mind. Not everything is black and white anymore. The Great Valu is no longer a grocery store; it’s where Grandmother McMullen’s house used to stand. Stargazer Floral is not just a flower shop on Main Street; it’s where Bobby Southard’s mother and Edieth Morris planted Lilies of the Valley together as a border between their two homes—the same lilies that were transplanted to Bobby’s house, and that he gave to Jeraldine when she moved back, saying, “I dug some of them up to welcome you back, neighbor.”

Kendall described it best when she commented, “Stories are what keep memories alive; they keep us in touch with the past and make our roots deeper. They tie families together and strengthen bonds.”

I may have lived in Greene County for eighteen years, but I never really saw it. The surface, maybe, but not the actual town. Not all history is happy; people struggle and there’s hurt, but fighting back is what makes it real. There’s no changing the past, but it’s not wrong to hold onto it, to be proud of it, and using it to become better. Reaching forward and building that house on the hill is what counts. ◊